Principal and Co-investigators

Dr Helen Johnson (PI)

Prof Heather Shore (Co-I)

Research Organisations

University of Hull

Leeds Beckett University

Hull History Centre

Funding sources

AHRC

Dates of funding

2017-2018

Our Criminal Ancestors was funded as a Follow-on project for impact and engagement by the AHRC, emerging from a successful Researching Networking Scheme entitled Our Criminal Past: Caring for the Future (AH/K005766/1). The Our Criminal Past research network successfully brought together academics from a range of disciplines (history, criminology, education, law, cultural studies) with those working in museums, archives and heritage sites in order to consider the preservation, presentation and dissemination of our collective criminal past: crime, policing and punishment records, collections, artefacts and the material culture of crime. The network and related activities provided a forum from which to explore ideas for new projects in and resources for the history of crime. The themes (digitisation and social media; education; display and representation) are identified important areas of cross and multidisciplinary interest in terms of existing and future research and as themes that have contemporary and cultural significance beyond the academy.

We successfully delivered three one-day events (in London, Leeds and Nottingham) as well as produced a special issue of the online journal Law, Crime and History devoted to Our Criminal Past. The issue brought together ten original journal articles developed from or invited after the seminars which were edited by the investigators.[1] The success of the research networking scheme also attracted members of the public to join our Twitter feed (@ourcriminalpast) or to enquire about activities, which led directly to the development of this public engagement and impact focused activity. The Our Criminal Past workshops (digitisation, social media, education, display and representation of crime history) clearly reached beyond the academic and heritage/curatorial audience. During the workshops the ‘public’ and public engagement was a frequent point of discussion – from how the public use criminal records, to how they interpret museum displays or use social media or digitised products – this then allowed us to develop this project which is directly about public engagement (Rogers, 2015).[2] There is also a great deal of general interest in social and family history, reflected in the worldwide success of television series like Who Do You Think You Are? (BBC, 2004 onwards) and most recently, The Secret History of My Family (BBC, 2016) (the first episode of which was based on the research of the CI). These programmes have featured stories that include convict transportation to Australia, imprisonment and court appearances. Other programmes have focussed more specifically on criminal ancestry; these include Secrets from the Clink (ITV, 2014) (which featured an interview with the PI) and Secrets from the Asylum (ITV, 2014). There is a clear public appetite for ancestral stories.

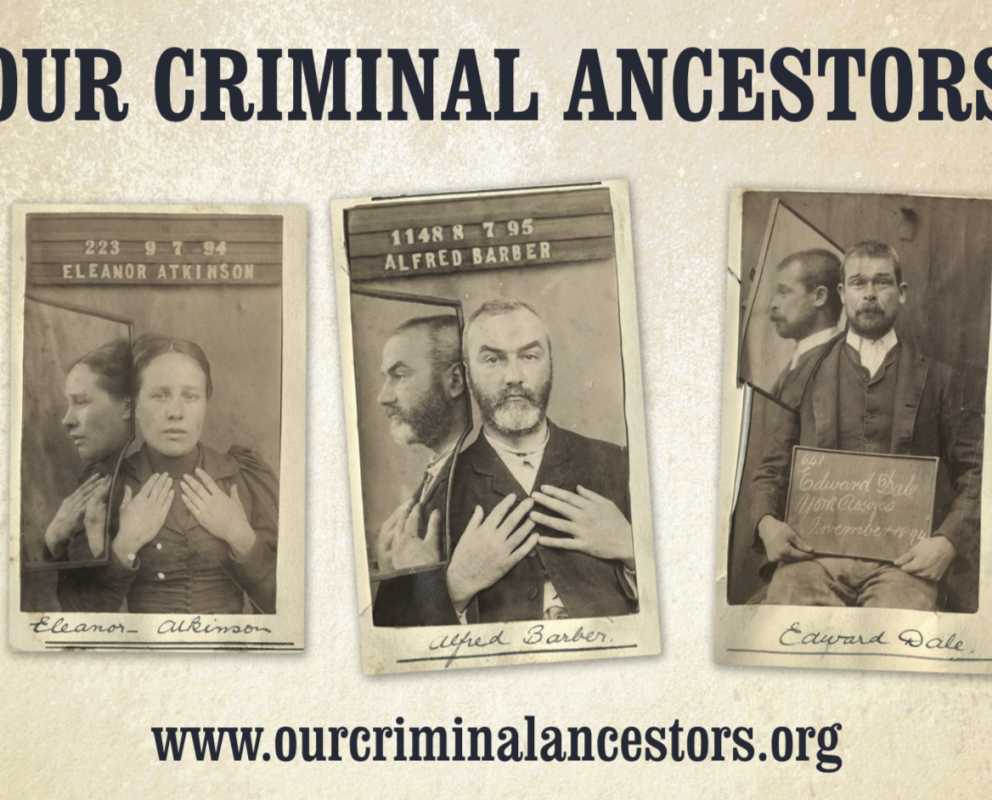

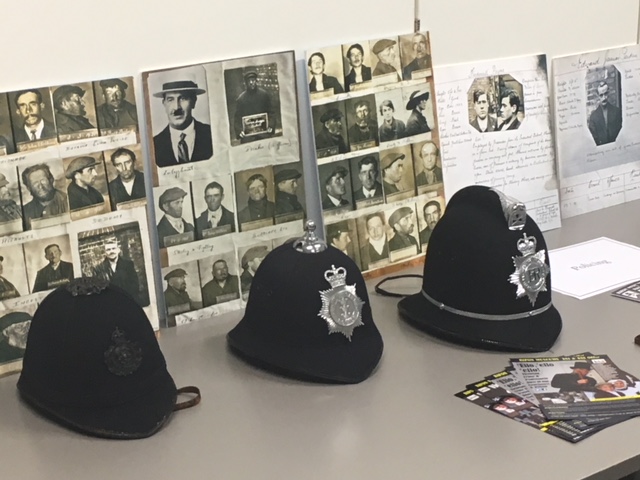

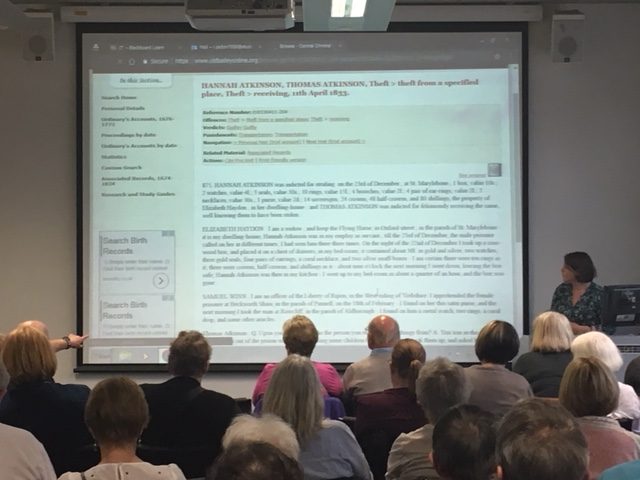

During the project, we have used the phrase ‘criminal ancestors’ as a generic phrase that refers to criminals, offenders and prisoners. But this term might also collectively refer to those who experienced the criminal justice system in different ways in the past, for example as victims or suspects, and those who worked within the criminal justice system, for example as police or prison officers, prison governors or court officials. Moreover, many individuals encountered the criminal justice system for relatively minor crimes and/or disorderly activities (vagrancy, alcohol-related offences and street rowdyism, for example). Crime history then offers a way into researching past lives that is not otherwise available. It is also a window into the lives of those from the working class or lower socio-economic groups who have left little evidence (beyond documents recording birth, marriage and death) and where information like witness statements or prison records can provide a valuable insight into society and everyday life. An important part of the project was also to help the public understand the context that may have caused their ancestors to commit crime, and to provide a more nuanced understanding of the past. An encounter with the criminal justice system may or may not have been a significant part of a person’s life, it may have been a singular occurrence in an otherwise law-abiding life.

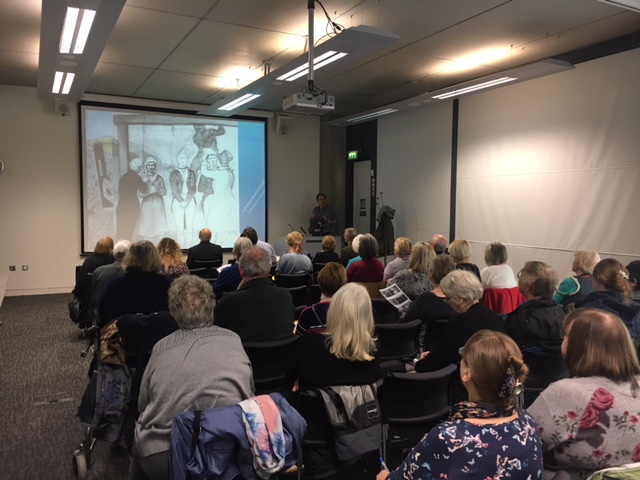

The main aim of the Our Criminal Ancestors project is to stimulate impact and facilitate creative public engagement with crime history through knowledge exchange, interactive workshops and website dissemination. We wanted to achieve this by engaging with our ‘criminal past’ as local communities, locally, regionally and nationally, primarily through collective interest in our criminal ancestors. Our aims were as follows: firstly to encourage and facilitate the public in finding, interpreting and using archival records to trace their criminal ancestors; secondly to promote creative interaction between academic researchers and the public, and thirdly, to disseminate the outcomes from this engagement through the project website. Hull’s City of Culture status provided an initial vehicle for the project but the research always envisaged a wider geographical focus. In order to achieve these aims we undertook the following activities:

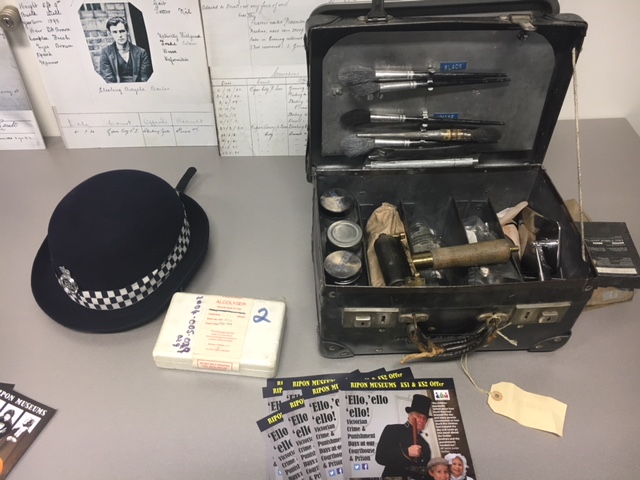

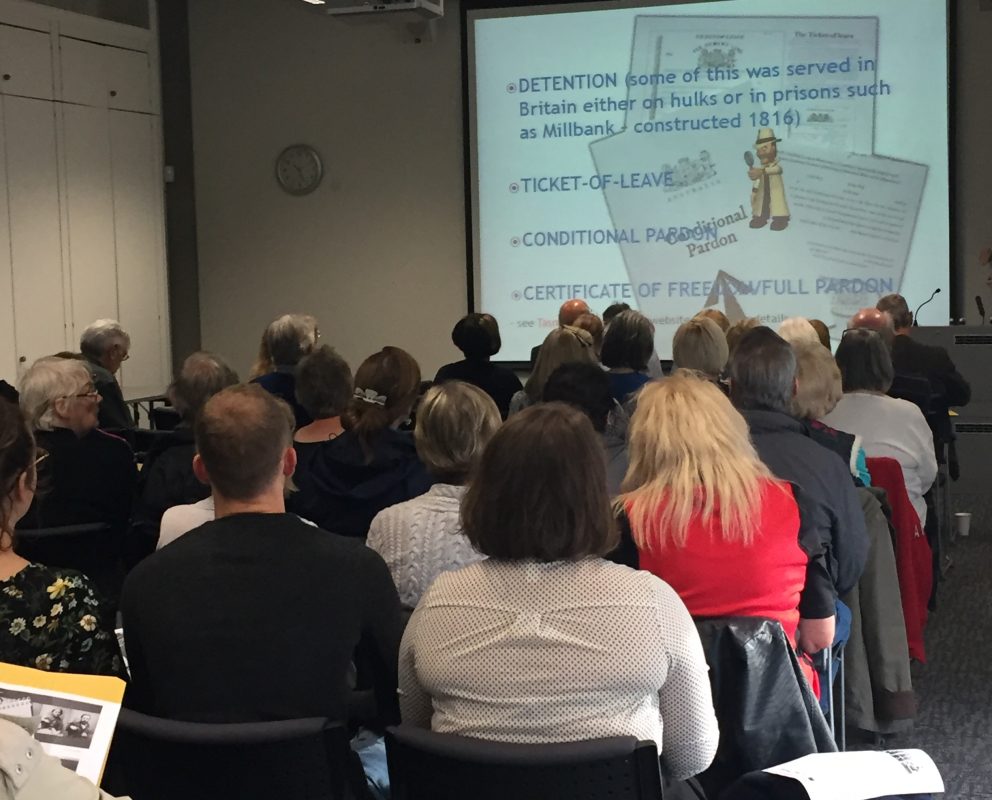

- Three interactive public engagement workshops with our partners, the Hull History Centre, during the City of Culture Year 2017, adding to the cultural and social activities across the city and with local communities and visitors to the year-long events. It also encouraged public interaction with digital history, thus fostering knowledge exchange and encouraging the development of new skills.

- Established an interactive and open access website which guides, assists and directs members of public, from across the World, with tracing their criminal ancestors in the UK – this provides free expert advice from leading researchers in the field. Social media exchange with researchers, other members of the public, short blogs based on their family or local research, and the mapping of their criminal ancestry will stimulate creative engagement and impact.

- Produced an accessible ‘Source Guide’ on the use of criminal records and identifying the national and most important local collections held at the Hull History Centre and at the East Riding Archives. This is available in hard copy but also available as a free pdf download.

- We also developed a blueprint for ‘Criminal Ancestors’ workshops and a source guide template. The workshops blueprint can be altered according to the type of public engagement event and the location and the source guide template could be adapted to work with any crime and punishment collection held at a museum, archive or heritage site across the country. This has provided an innovative, flexible, portable package that will facilitate future interactions and creative engagement with user communities.

During the project we further developed relationships with other archives, museums and heritage sites as well as family history societies and other organisations who were keen to work with us in a variety of ways. Therefore, we were also able to provide adapted workshops for East Riding Archives, Bradford Police Museum at Bradford Local Studies Library, Ripon Police and Prison Museum at Ripon Library. We have also provided expert talks to East Riding Archives, East Riding Family History Society, Preston Park Museum, Middlesbrough Courthouse, Leeds Museums and History Lab Plus and our research has also been featured in Who Do You Think You Are? Magazine. Our project has also recently been featured as a case study in new guidance document issued by The National Archives entitled Archives and Higher Education Collaboration Guidance 2018 Case Studies.

[1] H. Shore and H. Johnston (eds.), ‘Special Edition: Our Criminal Past: Caring for the Future’, Law, Crime and History, 5/1 (2015), pp.1-151.

[2] H. Rogers, ‘Blogging Our Criminal Past: Social Media, Public Engagement and Creative History’, Law, Crime and History, 5/1 (2015), pp.54-76.

Close