Madagascar in the World: Songs for Madagascar

December 2015 — September 2017

Principal and Co-investigators

Ulrike Meinhof (PI)

Research Organisations

University of Southampton

Funding sources

AHRC FoF

Dates of funding

2015-2017

Hi. I am Ulrike Hanna Meinhof, now a professor emeritus from the University of Southampton (Figure 1). Since 2002 I have been following the paths and interconnections of musicians of Malagasy origin in and across many sites in Madagascar and from there to Europe and Africa. I’d like to take you on a journey supported by the AHRC, that moved me from an academic research project TNMundi to a follow-on project reaching out to the general public with a full length music documentary. That film – Songs for Madagascar – produced in collaboration with award-winning director Cesar Paes from Laterit film productions shows the social commitment and movements of a group of musicians evolving from the project, The Madagascar All Stars.

The TNMundi project (Figure 2)

In collaboration with co-researcher Dr Nadia Kiwan and a research fellow Dr Marie-Pierre Gibert whose work concentrated on North African artists, our research offers alternative perspectives to migration and globalisation research. My own work focused on the mobilities of individual artists from Madagascar, connecting people and places in Madagascar with those in Europe, Africa and worldwide. It shows how migrants are often mis-represented in public and private discourses by ignoring their ‘transcultural capital’ and the benefit they offer to sending and receiving countries. Our analysis of the movement of artists identified particular socio-geographic spaces, individual people, and institutions as human, spatial and institutional ‘hubs’ that underpinned successful networking for many of the artists. But already with TNMundi we did not want to remain solely in the academic realm. Hence we integrated research symposia with cultural events for the general public. Curated by the Malagasy consultant to TNMundi, the musician Dama Mahaleo, we were able to attract a large general public, NGOs and the media in Antananarivo in 2007, in Rabat in 2008 and in Southampton in 2009. In this way our research reached out to the public whilst also supporting the emergence of a new group of engaged musicians around Dama Mahaleo, the Madagascar All Stars.

Madagascar in the World: The Impact of Music on Global Concerns

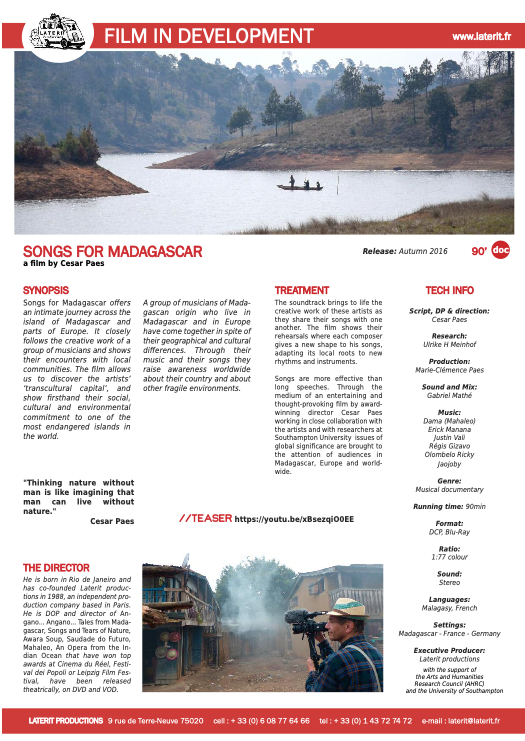

AHRC Follow-on Project 2015-17 (Figure 3)

Here the aim was specifically to translate the research results from the TNMundi project for a general audience through a full feature length documentary film Songs for Madagascar with bonus material. The film was realised as the interdisciplinary collaboration between myself as researcher, the film maker and producer Cesar and Marie-Clemence Paes from Laterit film productions, the project consultant and musician Dama Mahaleo, the musicians from the Madagascar All Stars and various NGOs and other contributors. With my full agreement there was to be no top-down voice-over explaining the theoretical and empirical outcome of the underlying research but instead the film should illustrate the activism and movements of the musicians through their music, their song lyrics and the concert-debates they engaged in. Rather than using explicit didactic commentary these different ‘bottom-up’ modes were to encapsulate key issues of environmental protection and the role of engaged diasporas in sending and receiving countries. This implicit approach raises the question as to the extent to which such themes are realised by the audiences. To find this out I followed up selected screenings in the first year of the film’s release by questionnaires in 4 different languages as well as question and answer sequences, and debates. Some of the results of this enquiry will be addressed at the end of this exposé.

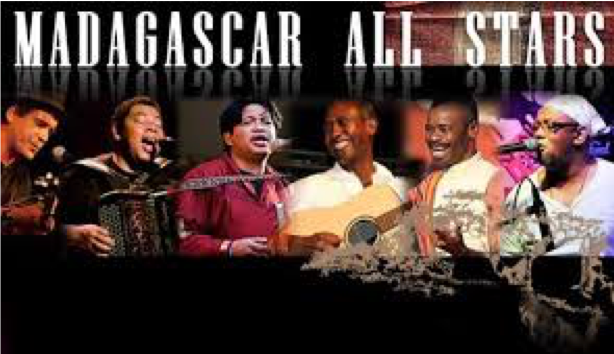

The Madagascar All Stars (Figure 4)

To appreciate the formation of this group of 6 musicians, each with their own solo careers, we need to be aware of the diversity of their background and the highly charged symbolic nature of their demonstration of ‘unity in diversity’. Madagascar has for many decades suffered tensions between the coastal regions and the highlands and there are large cultural differences between these and the North and the South. There are also different career paths for those musicians who left Madagascar to make their life in Europe and those who remained in Madagascar but only occasionally tour in Europe. Hence uniting in one group musicians who originate from the different regions in Madagascar and who live today in different parts of the world is meant to show national and transnational cultural diversity in a very different and positive light. With an origin from the Highlands of Madagascar we see on the picture Dama Mahaleo (4th from left) who lives in Antananarivo and Morondava, Erick Manana (1st from left) who lives in Berlin and Bordeaux, and Justin Vali (3rd from left) who lives in Lille. Originating from the South of Madagascar there is Regis Gizavo (2nd from left) who lived in Paris until his untimely death in 2017, Ricky Olombelo (1st from right) who lives in Antananarivo but with strong roots in the deep south), and with an origin from the north of Madagascar there is Jaojoby (2nd from right) who lives in Antananarivo and joined the group in 2015/2016 after the original group member Marius Fenoamby who lives in Paris left the group. The diverse composition of the group was an explicit aim of the musicians themselves – a making visible to Malagasies that there can be ‘unity in diversity’, and also a symbolic representation of the cultural benefits of diversity to everyone.

Producing the film Songs for Madagascar (Figure 5)

The key question for director and researcher in creating the film was how to translate academic analysis and data into a documentary film without a ‘top-down’ explanatory commentary. Certain pre-conditions need to be met right from the start, namely there has to be a high level of trust and friendship between director, researcher and the musicians since unless there is a willingness to adapt to very different perspectives and aims, accept compromise and resolve tensions such a project is bound to fail. So when I chose to collaborate with the film director Cesar Paes I knew from his previous films that he brought a very different tool-kit to my own analytical perspective.

Since there was to be no analytical commentary how could the film tell its own story bottom-up? If we follow the camera we can see all the following techniques in practice: first of all by giving a voice to the artists and local people, showing them in conversation or at press conferences, during debates; observing rehearsals where they were learning each others’ songs, and during concerts; letting them tell their life stories and concerns in interview mode or through the lyrics of their songs, that were sub-titled in several languages. But meaning is also made through diverse editorial techniques such as image, text and music interrelations and cuts that could link scenes in Madagascar with scenes in Europe thus underlining the transnational space in which the group operates. The fact that some of these musicians were migrants with the emotional burden of leaving their homeland emerged as part of their own narrative as well as the theme of some of their songs. Personal narratives, song lyrics and debates with the public highlighted that they shared the same concerns about the poverty and environmental damage of Madagascar as those in the group who continued to live in Madagascar, and illustrated the feasibility of a transnational public sphere of public engagement. And finally following two of the musicians on a journey by car, boat and on foot to a very remote part of the island where a group of local people are engaged in re-forestation and reclaiming their former territory. showed a natural landscape of great beauty as well as the danger of its destruction. It also raised hopes that the actions of engaged individuals can make a positive difference.

If we now look at three extracts from the film we can see how the film makes meaning by these various filmic means

Clip 1: Regis Gizavo (Figure 6 to play clip)

Themes raised include the following:

- Poverty creates very difficult conditions for people in Madagascar, here exemplified by a poor region in the south. The song by Regis Gizavo, Malaso, speaks about the ways in which corruption and crime makes the life a misery for cattle herders.

- For musicians and music professionals the capital Antananarivo is a passage obligé, a place of opportunity in the global South, whereas Paris functions as a similar hub in the global North

- Leaving Madagascar and making a living in Europe is a culture shock even for musicians who sees this as a major opportunity in their career, the need to adapt is painful, and for Malagasy the significance of rice is paramount so that its absence from a daily diet is harshly felt

- Regis’ song ‘Black is the colour of the drongo bird’ sends a strong anti-racist message in the disguise of singing about a Malagasy bird

Clip 2: Justin Vali with Dama in the van (Figure 7 to play clip)

Themes raised include the following:

- Many migrants from Madagascar – here the valiha player and singer Justin Vali – retain strong connections with their regions of origin and many are to-ing and fro-ing between their home villages and towns in Madagascar and Europe.

- Nostalgia for home remains very strong especially where people are forced by poverty to leave their homes

Clip 3: Ricky Olombelo (Figure 8 to play clip)

In this clip the film superimposes contrasting images over a song with explicitly political lyrics.

Themes raised include the following:

- There is wide-spread exploitation of Madagascar by multi-nationals. (In our research we had focused for example on the activities of Rio Tinto in the Fort Dauphin region where the exploitation of ilmenite took place in areas of primary forest by the sea and threatened the ecology of the forest and the livelihood of local fishermen).

- The clip shows conflicting images of beauty and poverty, where good technical provisions available to some individuals (e.g. laptops) are contrasted to the appalling state of the infrastructures

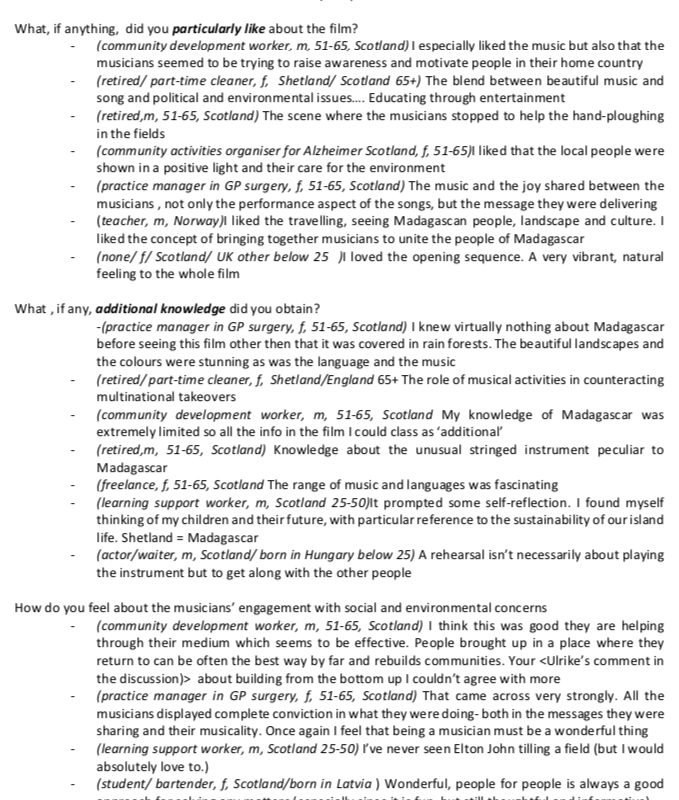

Screenings and audience reactions (Figure 9 to see audience reactions)

Between September 2016 and November 2017 selected screenings were followed by Question and Answer sessions and debates with the audiences. I was accompanied by the film maker Cesar Paes and/or the musician and project consultant Dama. Screenings included the Screenplay Festival, Shetland Islands September 2016; the Southampton Film Week, Turner Sims concert hall, November 2016; the Festival dei Popoli, Florence, November 2016; a film screening with a concert by the Madagascar All Stars in La Reunion, Feb 2017; Black International Cinema Festival , Berlin May 2017; a special screening at the Iwalewa House of African Art, Bayreuth, July 2017; the Festival du Insulaire de Groix, August 2017, and the Jean Rouch Festival, Paris, November 2017

The film was also released in cinemas from June 2017, on dvd in December 2017 and it continues to be screened until today.

Questionnaires were distributed in 4 different languages (English, French, German, Italian) depending on the film’s audience. They asked for anonymised biodata from the audience and then solicited 1 overall response (excellent to poor) to the film followed by 12 quantitative questions about responses to the content, the music and the images , with grades from 1 to 5, and 5 qualitative open questions about the major themes to elicit free commentary.

Evaluation

Conclusions from a detailed evaluation of the first six screenings (Shetland Islands, Southampton, Florence, La Reunion, Bayreuth, Berlin) were as follows:

- the film achieved its purpose of emotionally and intellectually engaging very diverse audiences with Madagascar, its music and the associated themes, especially in the need to protect the environment and in using art to do so.

- It aroused the audiences’ interest, achieved insights and a wish to know more (impact).

- The artists’ activism was overwhelmingly appreciated and endorsed although there was occasional scepticism as to the possibility of artists/ music making a difference.

- The Southampton and Florence audiences were the least interested in the passages filmed in Europe, whereas those in La Reunion and in Scotland were pronouncedly so.

The questionnaire also raised the topic of internal and international migration as a focus of the film. This was the least recognised theme by all the audiences, although it was appreciated during and after the debate.

Discussion

Why might there be such a lack of recognition of the migration theme?

As the subsequent debates showed, there is a prevalent image in public and private representations of migrants as needy refugees or dangerous troublemakers which does not fit the talented musicians featured in the film. Hence although the film meant to challenge such simplistic representations by showing migrant musicians as activist artists with an agenda shared by engaged people in Europe and Africa alike, the film does not sufficiently thematise that there is indeed an alternative view of migration to be recognised. Hence whilst the shared social, environmental, humanist, and non-racist values of the specific artists was appreciated it did not translate into a comment on migrants and their transcultural capital.

We identified this difficulty of recognising the contribution of migrants through a prevalent split between two contradictory discourses in public life:

On the one hand there is the discourse of the cosmopolitans – discourses of mobility with their association of the free flows of people, services and goods; on the other hand there is the discourse of migration which is a discourse of ‘the Other’. Here the cosmopolitan metaphors of free ‘flows’ are replaced by metaphors of waves and floods; masses overwhelming and threatening ‘our’ societies and way of life.

However the film works very strongly as a portrait of six engaged artists of Malagasy origin who through their music try to make a difference to some of the most important issues of our contemporary world.

Research publications (Figure 10 for full film credits and song Tsy Miraharaha with subtitles)

(2017) Globalized culture flows, transnational fields and transcultural capital. In A. Triandafyllidou (ed.) Handbook on Migration and Globalisation . Edward Elgar.

(2013) Cultural diversity in Europe: a story of mutual benefit. RSCAS publication. EUI

(2011) Cultural Globalization and Music. African Musicians in Transnational Networks. Palgrave (with Nadia Kiwan)

(2011). ‘Singing a new song? Transnational Migration, Methodological Nationalism and Cosmopolitan Perspectives. In special Issue Music and Migration. Music and Arts in Action : Vol 3, No 3 (with Nina Glick-Schiller)

http://musicandartsinaction.net/index.php/maia/article/view/singingnewsong

(2010). ‘Transnational musicians’ networks across Africa and Europe’. In K. Knott and D. McLoughlin (eds.) Diasporas: Concepts, Identities, Intersections. Zed publication. (with Gibert and Kiwan)

(2009) ‘Inspiration triangulaire: musique, tourisme et développement à Madagascar’. Numéro spécial des Cahiers d’études africaines : Mise en tourisme de la culture : réseaux, représentations et pratiques (with Marie-Pierre Gibert).

(2009) ’Transnational flows, networks and “transcultural capital”.Reflections on researching migrant networks through linguistic ethnography’. In Stef Slembrouck, Jim Collins and Mike Baynham (eds.) Globalization and Languages in Contact: Scale, Migration, and Communicative Practices. Continuum.

(2006) ‘Beyond the Diaspora: Transnational Practices as Transcultural Capital’, in Meinhof, Ulrike H. and Anna Triandafyllidou (eds.) Transcultural Europe. Cultural Policy in a Changing Europe. 200-222 (with Anna Triandafyllidou).

(2005) ‘Malagasy song-writer musicians in transnational settings’, Moving Worlds, 5 (1): 144-158 (with Zafimahaleo Rasolofondraosolo ).

(2005) ‘Initiating a public : Malagasy music and live audiences in differentiated cultural contexts’, in Sonia Livingstone (ed.), Audiences and Publics : When cultural engagement matters for the public sphere, Bristol-Portland, OR, Intellect : 115-138.

(2003), ‘Popular Malagasy music and the construction of cultural Iidentities’, in S. Makoni and U. H. Meinhof (eds), Africa and Applied Linguistics. AILA REVIEW, 16, 127–48. (with Zafimahaleo Rasolofondraosolo ).

This project is an AHRC Follow-on Project of:

TNMundi: Diaspora as social and cultural practice

Principal investigator: Ulrike Meinhof, University of Southampton

Co-Investigator: Nadia Kiwan, University of Aberdeen

Research orgs: Unviersities of Southampton and Aberdeen

Funding Source(s): For research AHRC, the Diaspora Migration and Identity programme

For cultural events: several funding bodies, most notably the Arts Council South-East (UK) , Goethe Cultural Institut (CGM, Antananarivo, Madagascar), Vazimba Productions (Antananarivo) Institut francais (Rabat, Morocco) British Council, Morocco.

Dates: 11/2006 – 3/2010

Close